Skills Don’t Transfer Themselves

Why trust and not just talent decides which of our abilities survive career transitions.

My Personal Reflections

My audio diary is my attempt to share a bit about my own experience through the lens of the themes and meta themes of the following essay. If you prefer to understand the material via stories, I invite you to listen. I also invite you to read the essay itself, too.

“Perhaps the most transferable skill is the ability to convince others you have transferable skills.”

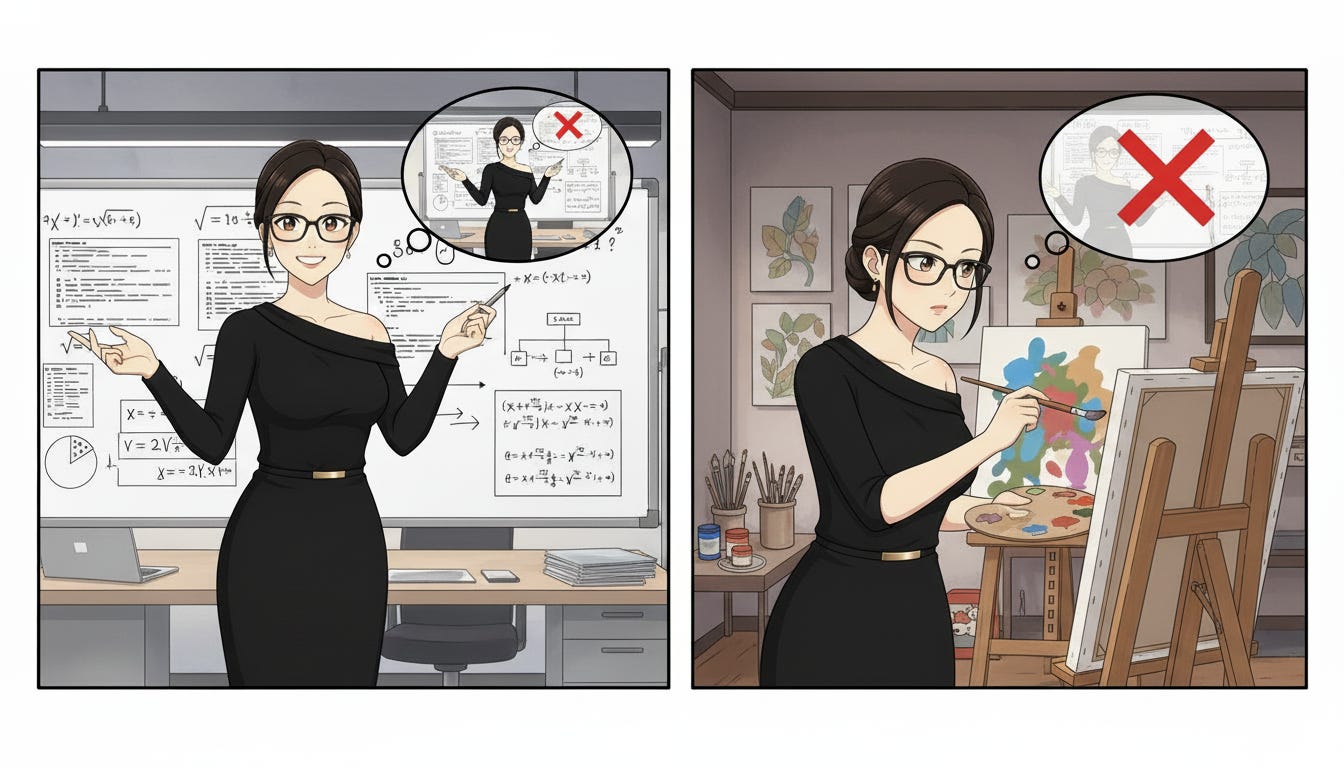

The Myth of Transferable Skills

We are often told that skills are portable, like luggage: pack them carefully, check them at the gate, and they will arrive safely wherever they are needed. But the world of work behaves less like an airport and more like a river that shifts course overnight, and no amount of preparation guarantees arrival. Industries rise and crumble in months. Job descriptions twist in ways that defy comprehension. The half-life of a skill that was once thought stable is measured in years, sometimes months, sometimes weeks.

Amid this churn, career advice insists on “transferable skills,” a phrase that carries promise and comfort. It implies stability: these abilities can leap cleanly from one domain to another. But the truth is less comforting. Transferable skills exist only when someone decides they do, when the observer is willing to bridge imagination with belief. Without that, even a perfectly executed skill is inert.

Skills as Performance

Richard Bolles, in What Color Is Your Parachute?, made the radical case that every experience can become professional capital. Volunteer work, hobbies, even playful or eccentric pursuits are reframable: leading a soccer team is leadership, organizing a community fundraiser is project management, running a role-playing game is facilitation. The idea is liberating: you are more than your job title.

But Bolles assumed a tidy world in which skills are like objects, stored neatly and transferable on demand. In reality, skills are rarely so static. They are performances: context-dependent, enacted, interpreted. A coder dropped into a chaotic startup may fail not from lack of ability but from lack of trust and recognition. A musician adapting to user experience design might possess relevant empathy and pattern recognition, but unless someone sees that capacity and believes in it, it is invisible.

Transferable skills, in practice, are not simply what you know. They are what others recognize and allow you to deploy.

The Power of Narrative

Daniel Pink in A Whole New Mind extends this idea, showing that empathy, storytelling, and human-centered thinking are not just “soft skills”; they are mechanisms to make performance legible. Skills alone, no matter how well executed, rarely transfer. They must be witnessed, interpreted, and endorsed. Narrative is the medium that converts competence into trust.

Consider a designer presenting a case study of an AI-enhanced product. The slides alone do not convey capability. But the story: the challenges faced, the iterations, the reasoning makes others see that the designer can think, adapt, and solve new problems.

This is where transferable skills live: in the interstitial space between demonstration and belief. It is social, relational, narrative. And, in a world increasingly populated by AI-generated outputs, it is also rare.

Generalist vs. Specialist vs. AI

In Range, David Epstein argues that generalists, who synthesize patterns across domains, outperform specialists in complex, unpredictable environments. But the world is skeptical. Specialization reads as credibility; generalism as ambiguity. Being broadly skilled is often indistinguishable from drifting.

AI intensifies this tension. It can produce polished outputs in seconds, flattening technical scarcity. What once demonstrated skill: the essay, the design mockup, the analytical report can now be machine-generated, making authentic human capability harder to signal.

Trust, not output, becomes the limiting factor. A generalist may possess immense latent capacity, but until someone vouches for it, the skill remains dormant. Adaptability is necessary but insufficient; it must be recognized, and recognition is social.

Identity and Risk

Herminia Ibarra, in her book Working Identity, has shown that career transitions are less about thinking into new roles than experimenting into them. Side projects, provisional roles, and experimental initiatives are laboratories for skill development. However, experimentation is risky. It exposes the self to half-credibility, misunderstanding, and sometimes outright rejection. Reinvention is emotionally costly. Burnout, self-doubt, and fractured identity accompany adaptability.

Even habits, the invisible scaffolding of skill, as Charles Duhigg notes in The Power of Habit are only valuable if their relevance is perceived. Discipline, consistency, and resilience built in one domain can underwrite performance elsewhere, but only if someone sees them and believes they are transferable. Skills, in other words, exist socially as much as individually.

Trust as the Scarce Currency

Trust is the medium through which transferable skills function. Credentials, titles, and portfolios were once sufficient proxies, but AI and the accelerated pace of change have eroded these assurances. Skills that were once signals become noise. Authenticity and credibility are increasingly rare and therefore valuable.

This is the paradox: the better your skills, the harder it may be to have them recognized. A generalist, a career-changer, a multi-disciplinary thinker may appear unfocused. A specialist may seem rigid.

In both cases, it is trust, the willingness of others to believe, that mediates the effectiveness of transferable skills. And trust is always conditional, always social, always hard-earned.

Narrative and Social Proof

If transferable skills are bridges, they are bridges built from perception and credibility rather than material. They require careful calibration: stories that demonstrate not just what was done, but how and why; endorsements that verify capacity; networks that amplify visibility. Narrative, observation, and relational proof convert potential energy into actionable value.

AI amplifies the stakes. It can mimic output, generate simulations, and accelerate iteration. But it cannot vouch for authenticity. It cannot convey character, judgment, or trustworthiness. In an AI-saturated world, the human elements of storytelling, empathy, and social credibility are not optional; they are the core currency that allows skills to cross domains.

Depth vs. Portability

Specialization provides legibility but sacrifices mobility; breadth offers adaptability but invites skepticism. Transferable skills exist in the tension between these poles, and navigating that tension requires careful signaling, deliberate narrative construction, and the ability to negotiate perception.

Adaptability alone is not enough. Success depends on making others believe in your adaptability, on translating latent potential into recognized capacity.

The Human Bridge

Transferable skills are neither magical nor self-evident. They do not exist in isolation; they travel only through social recognition, through trust, through narrative. AI may accelerate knowledge decay and create abundance of output, but it cannot manufacture credibility. In the end, the skill that matters most may not be what you can do, but whether anyone believes you can do it.

In the twenty-first century, careers are less about accumulating skills than building bridges of trust. Those who succeed are not merely adaptable; they are legibly human, capable of demonstrating their capacity, translating experience into narrative, and sustaining the fragile faith of those who witness their work. That is the true measure of transferability in an age of instability.